For the majority, the COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented situation. It has affected every sphere of life including work, education, leisure, and childcare. Parents have been more likely than non-parents to be furloughed and to have reduced income. Indeed, more than 30% of parents reported reduced income in the first three months of the pandemic, although this ratio had decreased to 17% by December 2020. What is more, parents changed their working patterns to adjust to home-schooling and childcare responsibilities. For some this resulted in doing their job in unsociable hours.

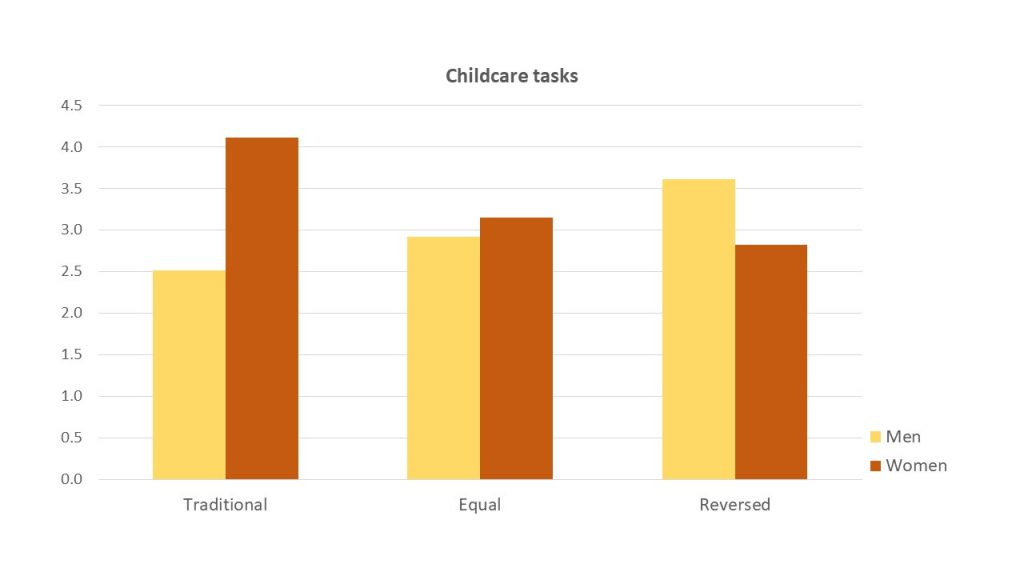

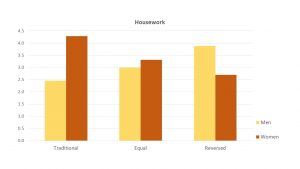

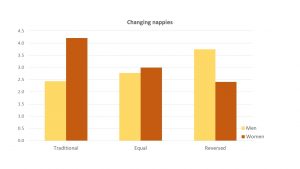

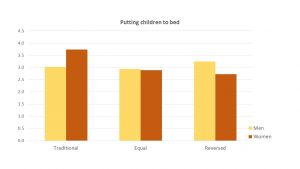

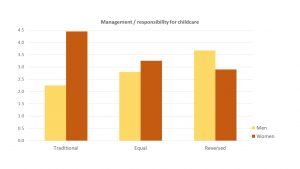

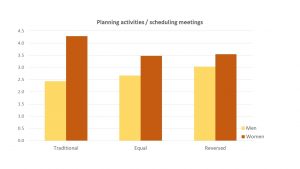

Childcare has traditionally been seen as a mothers’ duty although in recent decades a cultural shift towards involved fatherhood and the equal sharing of caregiving have been encouraged. According to ONS reports, throughout the pandemic women have spent more time than men on unpaid housework and childcare, particularly in families with younger children. These differences were even more pronounced in September-October 2020, despite the first lockdown coming to an end in July and children returning to school for the start of the new school year. At this time, parents started to spend more time working and less time doing housework or childcare duties. Importantly, women did more than men in terms of nurturing or non-developmental childcare (e.g. dressing, feeding, cuddling). Men and women contributed more equally to developmental childcare (e.g. reading, helping with homework) which they also found more enjoyable. However, this does not apply to the most recent lockdown where women have been more likely than men (67% and 52% respectively) to be involved in home-schooling. These figures suggest a worrying return to gendered divisions of labour but we continue to know little about couple decision-making or the lived experiences of men and women as they have navigated their family and work lives through the first year of the pandemic.

While our project is not focused on COVID-19 specifically we have asked the men and women in our study about how the pandemic might have affected the way they organise and share their work and childcare duties. So far, we have interviewed seven couples. Our participants reported some changes, although most of them did not consider them to be major. In general, the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have promoted more involvement in childcare by the parent who used to be less present due to work duties. In this way, couples who used to maintain distinct breadwinner-caregiver roles have become more balanced:

“Yes because he’s, he’s always here so he helps a lot with the, you know, lifts to the school or from school because he used to travel a lot. […] he wouldn’t spend so much time in the house so, you know, he’s more available which is good. He’s working the same hours but he’s around and it helps.” (Eva, 2 kids)

“Well because Julie was working at home, she hasn’t been leaving early in the morning so she’s been doing a bit more. Getting the kids ready for school and often she’s been picking them up from school because she’s been here and I’ve been working.” (Tom, 3 kids)

“We split things pretty much equally, especially since he started working from home after COVID […] But since September he’s been allowed to work from home, so I have someone to share that morning routine with now and it is just makes such a difference. […] Just having that backup, actually everything’s a lot easier since he’s been working from home.” (Kate, 2 kids)

In some cases, the pandemic appeared to have reinforced the existing traditional arrangements where a male is the main breadwinner and the female is the main caregiver:

“When the first lockdown happened, obviously I was completely off furloughed, Martin was then working from home. I stupidly thought that he would help out a little bit more… with more the schoolwork than anything else, which was the complete opposite. Uhm, even our eldest kind of said you know when daddy’s going to do some reading with me or when’s daddy gonna do some of the schoolwork with me? Why is it always mummy school? […] Whereas… like I, I started doing bins and things like that. So I suppose I ended up doing a little bit more in really trying to keep our youngest from constantly going into the office when he’s, when he was on work calls.” (Sophie, 2 kids)

Some of the parents highlighted the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on their children. They mentioned children worrying about their parent’s health, children’s education being interrupted and normal school being replaced by home-schooling, or that the pandemic had greatly restricted children’s usual activities, such as spending time outdoors, attending after-school clubs, visiting places, socialising:

“But they know that they can’t do their clubs and they can’t see their friends and their birthday parties were all cancelled and we can’t see their grandparents […] it’ll kind of bubble up and they’ll get upset.” (Kate, 2 kids)

Remarkably, parents tried to adjust to the demands of the situation, showing resilience and looking at the bright side. They acknowledged negative effects but also pointed to certain positive outcomes of the pandemic such as more flexibility at work and working from home which allowed them to spend more time at home:

“Thing is, if anything, it’s improved my work-life balance which is even better. Because I can be around the kids and work encourages, well, we had, in lockdown, would have team meetings where we bring the kids to the team meeting.” (Chris, 3 kids)

It is important to note that these interviews took place in November and December 2020, before the third lockdown. What is more, our participants so far have been relatively insulated, none has lost their job, and many were able to work from home. This may not be the case for others who are less well-positioned. In addition, some of the parents we interviewed explained that the restrictions were difficult psychologically as they limited people’s choice. Also, the closure of schools and childcare services posed a huge problem to those working from home:

“I prefer it [working from home] as long as the nursery stay open. It was incredibly difficult when the nurseries were closed because you were having to divide their time between working and ’cause I’m client facing, I’ll be on the emails and phone calls to people as well as having a 3 year old that is demanding and wants your attention. That was really, really, really difficult.” (Hannah, 1 kid)

More broadly, ONS reported that although in the last few weeks people’s well-being has improved slightly, happiness and life satisfaction have remained low while anxiety has been much higher compared to the pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, home-schooling placed a lot of strain on parents. With the school closure in January, a higher number of parents than in the first lockdown (April-May) declared that home-schooling negatively affected their and their children’s wellbeing, as well as their job and the relationships with others in the household. Therefore, it will be particularly interesting to learn more about how the third lockdown affected parents and their arrangements of work and childcare duties.

One of the quite clear effects of the pandemic is that parents have been involved in home-schooling and had no time for other things, including taking part in research studies. But as the schools are open again, hopefully, we will be able to attract more participants and learn more about parents experiences during COVID-19 pandemic and in general. We are particularly interested in the experiences of families where the fathers do as much, or more caregiving than their partners. If you and your partner would like to take part in our project, click here or email Agata at awezyk@lincoln.ac.uk to find out more